The Hierarchy of Objectivism, Part 1

Post on the fifth chapter in Leonard Peikoff’s book "Understanding Objectivism", “The Hierarchy of Objectivism”.

Disclaimer: I’m not an expert on philosophy. I’m just a person trying to figure things out for myself, and speak for no one but myself.

This post is about Lecture Five, "The Hierarchy of Objectivism", in Leonard Peikoff’s book Understanding Objectivism. I’ll go through the chapter, summarizing and adding my own thoughts, comments, or questions.

Peikoff says that all knowledge is built on a hierarchical structure and that knowledge isn't a grab bag of disconnected items we can learn about in any order. He then says that knowledge "has a logically necessary order." I think that as a practical matter you need some organized approach to a topic, and certain approaches are going to be better than others in most cases (e.g. starting with addition instead of starting with calculus). Organization is important. One of the things that's come up repeatedly in the presentations people have given on various topics throughout the book is that people lose track of where they are in their analysis and what they're arguing, and so they just start giving a recounting of Objectivism, which comes off as unpersuasive, because it's just a disconnected grab bag of stuff that's only tangentially related to the topic at hand. I think "logically necessary order" is false, though. That's saying that the laws of logic don't permit certain orderings or organizations of knowledge, and I'm not sure what Peikoff would base that claim on. There are lots of criticisms you can make of certain organizations/approaches to knowledge (inefficient, confusing, counterintuitive) without needing to bring the laws of logic into it.

Peikoff talks about the benefits of his approach:

So when you have the hierarchy of any item of knowledge set out before you, you know the anatomy of how you acquired that item of knowledge. You have its cognitive pedigree—where it came from, what it depends on—and thereby you are able to grasp its proof, how you know it is true. Once you set out its hierarchical base or roots, you can then say, “So and so and so, the earlier points are the things on which it depends, and by reference to which it can be established.” You want to prove this item? Then this is what you have to first establish, because that’s what leads to it. You want to understand this item? Since this is the point at which it arises, all these earlier points are its context; that’s what you must assume and that’s what you must count on when you are trying to chew it. This is true of any item in any field.

I think Peikoff's discussion here shows the value of trying to organize your knowledge in a hierarchy. If you have a clear hierarchy in your head, then you have a good idea of what your background assumptions are and where you are in trying to make your argument. And if something is going wrong — like the argument you are trying to make is fuzzy and unpersuasive — then you have some specific, defined places to look for problems. You can just look for problems in the context for the specific "floor" you're at in your hierarchy of knowledge. If your knowledge is really disorganized and you're trying to make some argument by making big claims about every semi-related topic you can think of, and you run into trouble in making that argument, then you could have to search across a huge array of your knowledge for potential problems. An analogy might be that a person with organized knowledge can look at the floor "below" their current argument if they are having problems, and just keep looking at the floor below and the floor below that if they can't find the issue right away. A person with disorganized knowledge, however, might be looking all over the building and even in different buildings. An example of this issue came up in a previous post when discussing why force was wrong. In making that claim, you might argue that force is anti-independence and anti-long-range and anti-principles and various other things. And so if you run into trouble being persuasive on that point, you've got to search for problems across your ideas about independence and the importance of long range action and the importance of living according to principles and whatever else you decide to bring up. That's a lot of material to review for errors in your understanding, and a lot of it might only be tangentially related. OTOH, if you argue for why force is wrong along the lines Peikoff does — it's wrong because you cannot force a mind, but you can force behavior and thus make the mind impotent, and since your mind is your means of survival, then force is anti-mind — then the scope of stuff you have to troubleshoot if you are having difficulty with the argument is relatively limited, and all of it is essential to a tightly-formulated argument.

Peikoff says we're going to consider the hierarchy of philosophy in particular. He says that in reality, all philosophic truths are simultaneous. There isn't a hierarchy in reality.

Hierarchy is an epistemological issue, not a metaphysical one. For instance, suppose I asked you the question, “Which comes first in reality, A is A, or man is a rational being?” You couldn’t possibly answer that question because “man is a rational being” is the statement of one specific identity, and “the law of identity” is merely the general statement that everything has a specific identity; the law of identity has no content apart from all its instances, and its instances are instances of it. You couldn’t possibly say that specific identities come first in reality, and then a month later, the law of identity comes, or vice versa; they are simultaneous in reality, metaphysically.

I agree so far.

But, if we want to grasp these two propositions, then we have to grasp the law of identity before we grasp that man is a rational being. Why? Because in order to grasp that man is a rational being, we must first have some knowledge of the basic principles of logic, in order to guide our thought. So we have to—not necessarily explicitly, but at least implicitly—grasp the law of identity close to the outset in order to be able to go on, form concepts, form definitions, and so on, and one day rise to grasp the definition “man is a rational being.”

I'm not convinced of this. Peikoff says that we need to at least implicitly grasp the law of identity close to the outset in order to be able to go on and form concepts and definitions and so on. But I thought we were talking not of implicit grasping but rather of explicit step-by-step hierarchy building. If we're including implicit assumptions that are necessary, I think one could reasonably argue that we implicitly rely on the rational capacity of man in even trying to formulate arguments and grasp concepts (in general, about any topic) in the first place. In formulating arguments and grasping concepts, we definitely don't act as if man lacks a rational capacity!

A separate point is that the law of identity is actually an enormously abstract idea — much more abstract, in my opinion, than the idea of humans as rational beings. So humans as rational beings might be a reasonable starting point. One can see many examples in the world of individuals demonstrating what seems to be a rational capacity, or of them violating or contradicting that capacity. "The law of identity" or "A is A" seems like a much more abstract thing to me than the claim that man is a rational being. So I think that one reasonable approach to learning about philosophy could start with thinking about human action and what people try to achieve in the world — their goals and values — and why some people succeed and some people fail. One could consider lots of specific cases and examples. And one could work one's way from there to the issue of virtuous and problematic ways of thinking and living, and how those ways of living reflect fundamental truths about reality (such as objective reality, the law of identity and so on). I think a reader might experience Rand's novels as basically taking this approach. In both Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead, the longest philosophy speeches came after hundreds of pages of plot and characterization showing, mostly implicitly through characters' thoughts/speech/actions, different ways of living and the success or failure of those ways of living.

To be clear, I think there is value in the way Objectivism organizes philosophy in terms of starting with stuff like A is A. Objectivism wants to emphasize certain important themes and ideas such as the objective existence of reality and the importance of non-contradiction, start from there, and work its way up to other things. But I don't think it's an example of a logically necessary order. That's not a criticism of Objectivism or of the approach to organizing topics Peikoff is arguing for. An ordering doesn't have to be logically necessary in order to be fruitful/worthwhile/good/worthy of study.

Peikoff says that there are some options even if the overall structure is logically dictated. He gives an example of organizing rationality, independence, and integrity. According to Peikoff, independence and integrity are both concretizations of rationality so they're on the same "level".

Peikoff says it's important not to confuse the issue of hierarchy with the issue of childhood development. He says you might learn about integrity before thinking about the standard of value or other pieces of data "without its hierarchical base." He says that's fine but there's a difference between that sort of thing and needing to e.g. prove that integrity is a virtue. I think Peikoff's discussion here illustrates something I find problematic about his whole approach. In an earlier post I quoted Peikoff as saying:

Proof is really nothing but taking an abstract idea and endowing it with the vividness, the immediacy, the compelling quality of the percept of the truck that we talked about.

And I took that as Peikoff saying that he wasn't "talking about things in the vein of formal logic or math proofs or anything like that." But I think this desire for a tight logically necessary structure to the organization of philosophical topics is motivated by wanting something more formal and rigorous than just a really persuasive argument.

Peikoff says that while there are technical fine points you can discuss back and forth for hours, his purpose in the present lecture is go over the essentials. So he gives the following exercise:

Here is the exercise on the hierarchical relation of the ideas in Objectivism. I have distributed a sheet [see below] with twenty different statements or topics, deliberately in an utterly random, senseless order. I want you to number them logically from one to twenty; the more fundamental, the more primary, the smaller the number. There are options. There are certain cases where you have a choice, which is one of the significant things in this exercise, which we want to point out in contrasting Objectivism to rationalism. I made this relatively easy. I left out a lot of tricky ones, and after we go through the order of this twenty next time, I’m going to throw them at you one new one at a time, and you tell me, would it go between four and five, or nine and ten, or whatever, where would it go? And we’ll get more and more tricky as we go, until hopefully you’ll have a real sense of the hierarchical structure.

[The exercise distributed to the attendees two weeks earlier:]

Capitalism as the only moral system.

Romanticism as the conceptual school of art.

A is A.

The virtue of independence.

The evil of the initiation of force.

Knowledge as objective (versus intrinsic or subjective).

The senses as valid.

Existence exists.

The virtue of honesty.

Concepts as identifications of concretes with their measurements omitted.

The integration of man’s mind and body.

The validation of individual rights.

Consciousness as the faculty of perceiving that which exists.

The nature of art, and its role in man’s life.

Reason as man’s only means of knowledge; reason versus mysticism.

Reason as man’s means of survival.

The proper functions of government.

Rationality as the primary virtue.

The law of cause and effect.

Man’s life as the standard of moral value.

Alright, let's try putting these in some kind of reasonable order. I don't expect my ordering to be very good but am curious how wrong I am, so let's try it (I did this pretty quickly based on existing intuitions):

- Existence exists.

- Consciousness as the faculty of perceiving that which exists.

- A is A.

- The law of cause and effect.

- The senses as valid.

- Reason as man’s only means of knowledge; reason versus mysticism.

- Concepts as identifications of concretes with their measurements omitted.

- Knowledge as objective (versus intrinsic or subjective).

- The integration of man’s mind and body.

- Man’s life as the standard of moral value.

- Reason as man’s means of survival.

- Rationality as the primary virtue.

- The virtue of independence.

- The virtue of honesty.

- The evil of the initiation of force.

- The proper functions of government.

- Capitalism as the only moral system.

- The validation of individual rights.

- Romanticism as the conceptual school of art.

- The nature of art, and its role in man’s life.

Peikoff asks audience members to discuss their guesses and comments on them.

I got the order of the first three correct according to Peikoff. Regarding #4, the law of cause and effect, Peikoff says that's possible on the grounds that the law of cause and effect is a corollary of the law of identity, but that putting it at #4 would not be his preference. Peikoff would put " Reason as man’s only means of knowledge; reason versus mysticism" at #4. He wants to put the big picture principle of epistemology first and then the corollaries after the principle. Following that approach, he puts "The senses as valid" at #5, "Concepts as identifications of concretes with their measurements omitted" at #6, and "Knowledge as objective (versus intrinsic or subjective)" at #7.

Peikoff explains that the basic method is as follows for each field: first you set out the basic principle. Then you set out the details that chew it. Then you set out some generalities that summarize it. He says that in the area of politics, the fundamental is rights, and the generalities are things related to the practicality of capitalism. And in ethics, the fundamentals are life as the standard and rationality as the fundamental virtue, and the specific applications of rationality (the virtues) are the details, and the summarizing generality is that the moral is the practical. This reminds me a bit of the IRAC method you learn in law school – the issue is the general topic area (metaphysics, epistemology), the rule is the basic principle, the application consists of the details you are chewing, and the conclusion is the summarizing generality.

Peikoff puts the law of cause and effect at #8. Then he continues on to a topic he says is in between metaphysics and epistemology. He calls this "the metaphysical or essential nature of man." He says the fundamental principle here is "Reason as man's means of survival." I was putting that under ethics and not as a separate subtopic. Peikoff says that the distinction between "Reason as man's means of survival" and "Reason as man’s only means of knowledge" is that the latter is purely epistemological and doesn't address the issue of life, but man is a living entity and thus needs some means of survival. Peikoff says there's some option as to whether you put "The integration of man’s mind and body" or "Reason as man's means of survival" first depending on how you are interpreting "mind and body". He interprets it as being about the integration of thought and action or theory and practice – an implementation of the idea that reason matters in a person's everyday life – and so he interprets it as being a specification of reason as man's means of survival.

Next comes ethics – the base is "Man’s life as the standard of moral value" (#12) and next is "Rationality as the primary virtue." He says that there's a total option regarding the virtues of independence and honesty -- either one can come first. So those are 13 and 14 respectively. And then comes "The evil of the initiation of force". With the virtues having been established, we can consider what contradicts those virtues, and so we consider the evil of force.

Peikoff says that there's an option regarding the next general topic, since politics and esthetics don't presuppose each other. If you go with politics, then "The validation of individual rights" comes next (#16). I put that towards the end of politics. I think I was thinking of "individual rights" as the technical details of implementing rights (like, free speech, property) and "validation" as something you'd do after having established some other steps in an argument, but Peikoff is thinking of it as the basis for the whole topic of politics. Peikoff agrees that "The proper functions of government" and "Capitalism as the only moral system" go in that order. Then come esthetics.

Peikoff's order:

- Existence exists.

- Consciousness as the faculty of perceiving that which exists.

- A is A.

- Reason as man’s only means of knowledge; reason versus mysticism.

- The senses as valid.

- Concepts as identifications of concretes with their measurements omitted.

- Knowledge as objective (versus intrinsic or subjective).

- The law of cause and effect.

- Reason as man's means of survival.

- The integration of man’s mind and body.

- Man’s life as the standard of moral value.

- Rationality as the primary virtue.

- The virtue of independence.

- The virtue of honesty.

- The evil of the initiation of force.

- The validation of individual rights.

- The proper functions of government.

- Capitalism as the only moral system.

- The nature of art, and its role in man’s life.

- Romanticism as the conceptual school of art.

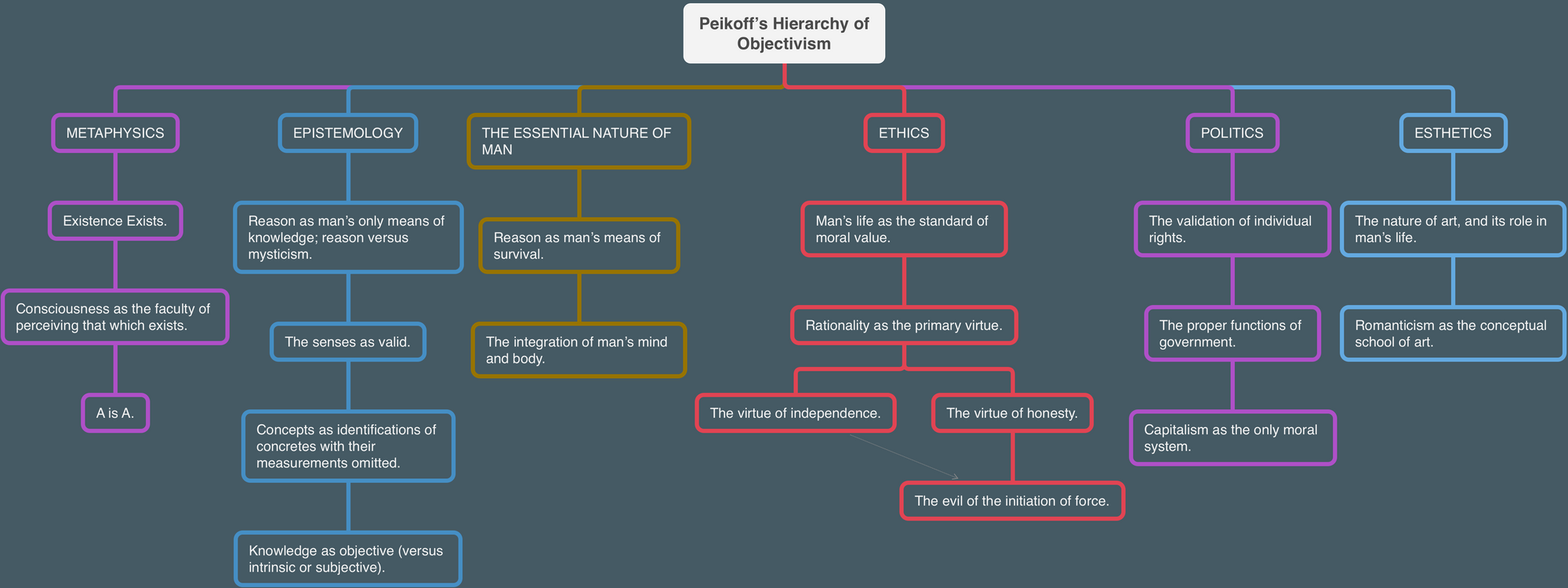

And here is a tree (to be read from left to right and then from top to bottom within each topic):

Peikoff has some more material on this exercise which I'll address in my next post.