Error in Stoicism Book?

A post respectfully suggesting that there may be an error in a book about Stoicism.

From A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy by William B. Irvine:

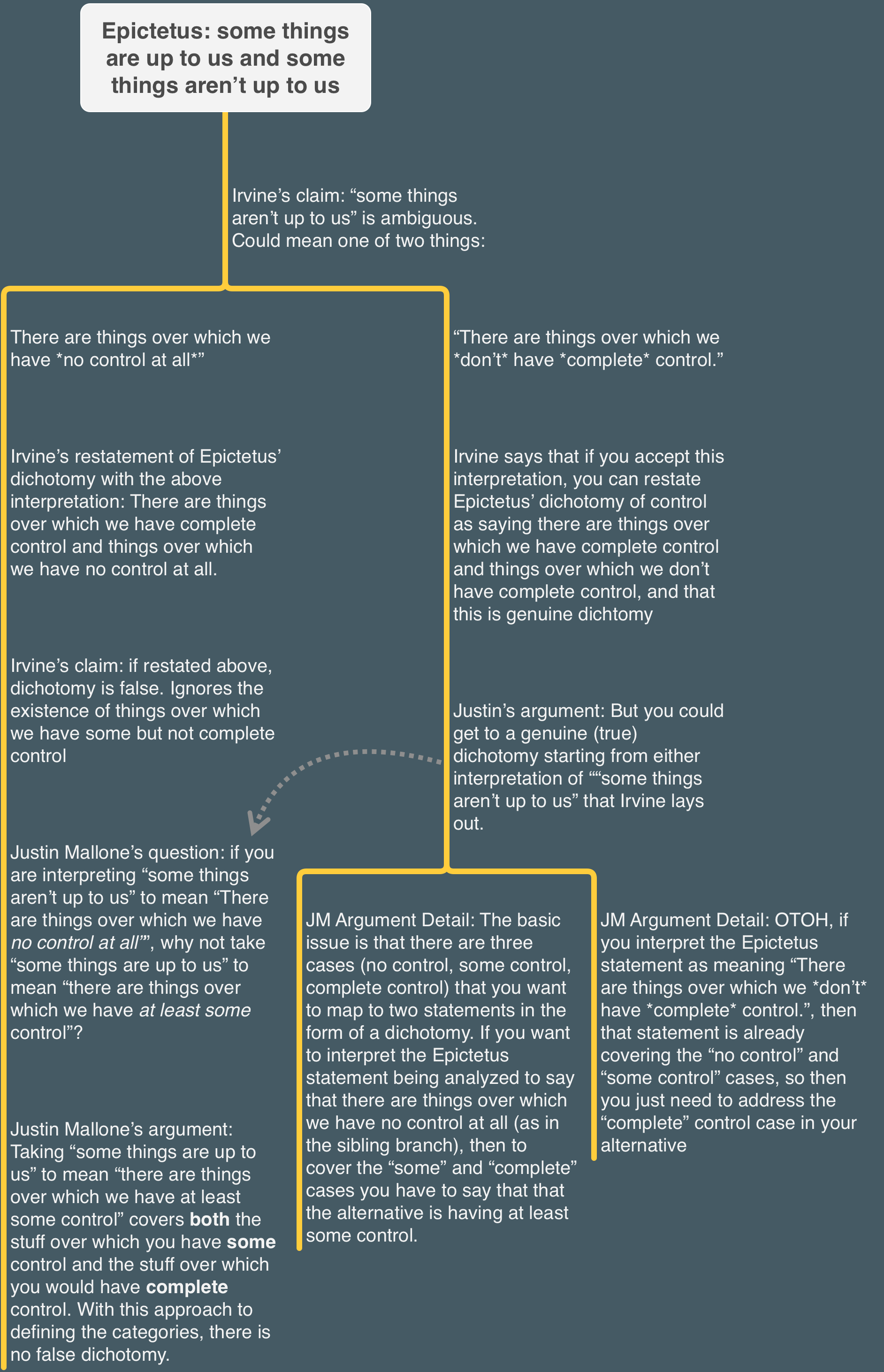

CONSIDER AGAIN Epictetus’s “dichotomy of control”: He says that some things are up to us and some things aren’t up to us. The problem with this statement of the dichotomy is that the phrase “some things aren’t up to us” is ambiguous: It can be understood to mean either “There are things over which we have no control at all” or to mean “There are things over which we don’t have complete control.” If we understand it in the first way, we can restate Epictetus’s dichotomy as follows: There are things over which we have complete control and things over which we have no control at all. But stated in this way, the dichotomy is a false dichotomy, since it ignores the existence of things over which we have some but not complete control.

Consider, for example, my winning a tennis match. This is not something over which I have complete control: No matter how much I practice and how hard I try, I might nevertheless lose a match. Nor is it something over which I have no control at all: Practicing a lot and trying hard may not guarantee that I will win, but they will certainly affect my chances of winning. My winning at tennis is therefore an example of something over which I have some control but not complete control.

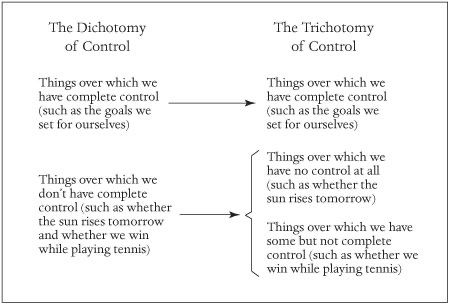

This suggests that we should understand the phrase “some things aren’t up to us” in the second way: We should take it to mean that there are things over which we don’t have complete control. If we accept this interpretation, we will want to restate Epictetus’s dichotomy of control as follows: There are things over which we have complete control and things over which we don’t have complete control. Stated in this way, the dichotomy is a genuine dichotomy. Let us therefore assume that this is what Epictetus meant in saying that “some things are up to us and some things are not up to us.”

Now let us turn our attention to the second branch of this dichotomy, to things over which we don’t have complete control. There are two ways we can fail to have complete control over something: We might have no control at all over it, or we might have some but not complete control. This means that we can divide the category of things over which we don’t have complete control into two subcategories: things over which we have no control at all (such as whether the sun will rise tomorrow) and things over which we have some but not complete control (such as whether we win at tennis). This in turn suggests the possibility of restating Epictetus’s dichotomy of control as a trichotomy: There are things over which we have complete control, things over which we have no control at all, and things over which we have some but not complete control. Each of the “things” we encounter in life will fall into one and only one of these three categories.

I think that Irvine may have made an error here, but it’s a bit tricky so I’m not sure. Feedback appreciated.