Cognitive Distancing & Stoicism Comments

Some comments on a Stoicism book's discussion of cognitive distancing

Quote from Donald J. Robertson's How to Think Like a Roman Emperor:

Moreover, Epictetus told his students that one of the Stoics he held in particularly high regard, Paconius Agrippinus, used to write similar letters to console himself whenever any hardship befell him.33 When faced with fever, slander, or exile, he would compose Stoic “eulogies” praising these events as occasions to exercise strength of character. Agrippinus was truly a master decatastrophizer. He would reframe every hardship as an opportunity to cope by exercising wisdom and strength of character. Epictetus says that one day, as Agrippinus was preparing to dine with his friends, a messenger arrived announcing that the Emperor Nero had banished him from Rome as part of a political purge. “Very well,” said Agrippinus, shrugging, “we shall take our lunch in Aricia,” the first stop on the road he would have to travel into exile.34

Marcus tends to refer to this way of viewing events as entailing the separation of our value judgments from external events.

This is discussing an objective perspective on events that lets you not get so upset by them. I think the idea of separating value judgments from external events isn't quite the right way to think about the issue. The issue isn't a bare value judgment that something is bad. The issue is the value judgment that something is bad combined with the judgment that the appropriate way to feel about a bad thing happening is sad, upset, angry, or another problematic emotion. You could judge something as bad/wrong/problematic/screwed up/unfortunate and not get upset by it. You could, for instance, think that your portfolio taking a downturn is unfortunate without getting emotional about it. I think that's a good example, since lots of people are fairly detached about how their portfolio is doing, but some people get very emotional and wrapped up about it, which shows that a range of reactions and perspectives are possible.

Cognitive therapists have likewise, for many decades, taught their clients the famous quotation from Epictetus: “It’s not things that upset us but our judgments about things,” which became an integral part of the initial orientation (“socialization”) of the client to the treatment approach. This sort of technique is referred to as “cognitive distancing” in CBT, because it requires sensing the separation or distance between our thoughts and external reality. Beck defined it as a “metacognitive” process, meaning a shift to a level of awareness involving “thinking about thinking.”

“Distancing” refers to the ability to view one’s own thoughts (or beliefs) as constructions of “reality” rather than as reality itself.35

[snipped content]

Sometimes merely remembering the saying of Epictetus, that “it’s not things that upset us,” can help us gain cognitive distance from our thoughts, allowing us to view them as hypotheses rather than facts about the world. However, there are also many other cognitive distancing techniques used in modern CBT, such as these:

• Writing down your thoughts concisely when they occur and viewing them on paper

• Writing them on a whiteboard and looking at them “over there”—literally from a distance

People are very identified with the content of their thoughts. They lack any objective perspective on or separation from their thoughts. Given that, some exercises that seem fairly simple and crude can help. That's why people physically separating themselves from an expression of their thought (on paper, on a whiteboard) can be helpful.

• Prefixing them with a phrase like “Right now, I notice that I am thinking…”

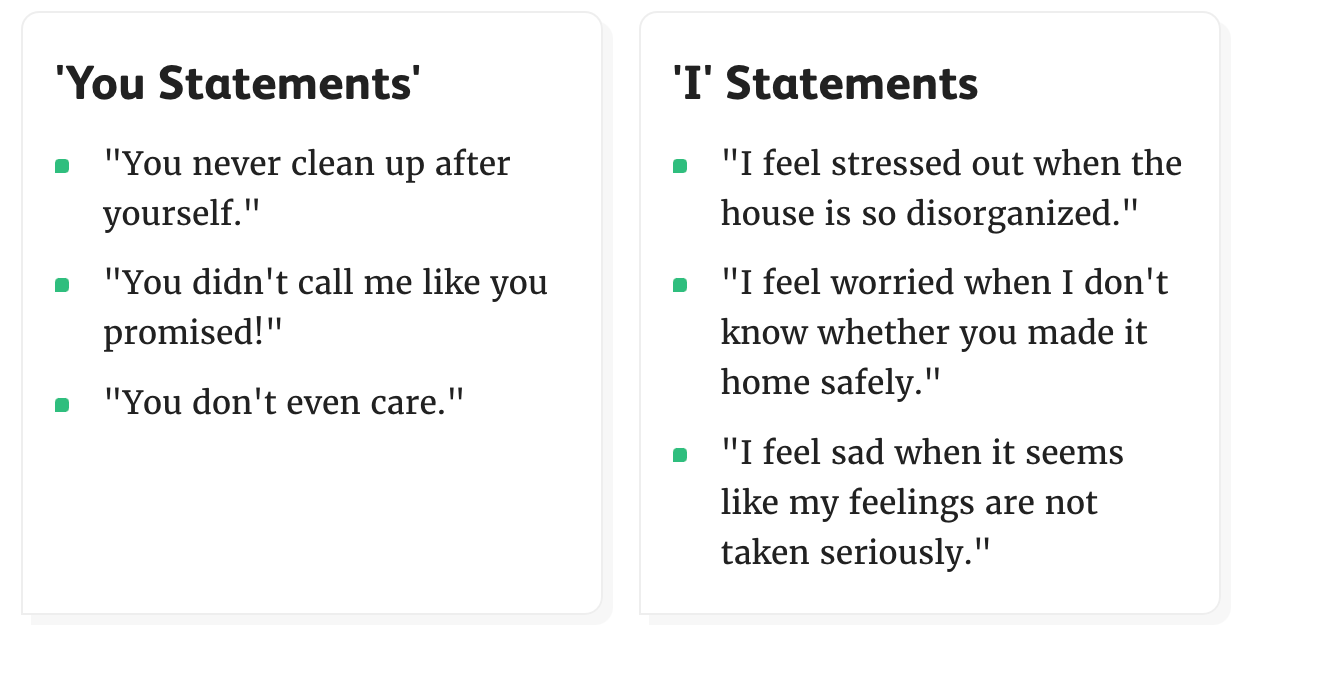

This is kind of similar to "I feel" statements. In the "I feel" statement context, you're trying to make statements said to other people less confrontational/judgmental by framing them in terms of your emotions.

People are often very harsh and negative towards themselves – often they're the harshest towards themselves. So "I notice that I am thinking" statements can, as one example, help you get some distance from your own harsh judgments about yourself. So "I feel" is about trying to treat other people nicer, and "I notice that I am thinking" can help you treat yourself nicer.

When people have emotional problems, they often think things like "I am a complete failure." If they don't have any separation from that thought, then they can become stuck in a loop thinking that and similar thoughts. But "I notice that I am thinking that I am a complete failure" is already pushing the thought away a bit. It's an observation, not a direct expression of a judgment. And even with that tiny bit of "cognitive distance", it might be easier to realize that you're exaggerating – that you're not a complete failure, even if various aspects of your life aren't what you want them to be.

• Referring to them in the third person, for example, “Donald is thinking…,” as if you’re studying the thoughts and beliefs of someone else

Often people are good at seeing problems or mistakes in other people's thinking while having huge blindspots about their own issues. Given that, it makes sense that trying to put yourself into more of the "other person" box could be helpful.

• Evaluating in a detached manner the pros and cons of holding a certain opinion

One practical application of this one for me: if some project you care about seems unlikely to succeed, and you assume that it won't and act accordingly, you might miss out on an opportunity to make it work. If you assume it might succeed and act accordingly, you might figure out a way to make it work, or get lucky, or whatever. So pessimism in this case seems worse than optimism. Now, that's a broad, sweeping assertion, and there are ways to criticize it if interpreted a certain way (e.g. imagine someone working really hard to make their lottery-winning project succeed). But, if you take it as involving a decent-enough project where there's some non-trivial amount of success, and assume the person doesn't have a better project they could jump to, and make various other assumptions, I think it's reasonable. And it's the sort of idea that can definitely help someone who gets stuck in pessimism doom-loops.

• Using a counter or a tally to monitor with detached curiosity the frequency of certain thoughts

I like this one. I think that I'm going to try incorporating this one into my daily practice a bit. I suspect that, even for thoughts I know are a problem, the frequency of certain thoughts will still surprise me. The only problem I see is how to accurately keep a tally of how often a thought comes up.

• Shifting perspective and imagining a range of alternative ways of looking at the same situation so that your initial viewpoint becomes less fixed and rigid. For example, “How might I feel about crashing my car if I were like Marcus Aurelius?” “If this happened to my daughter, how would I advise her to cope?” “How will I think about this, looking back on events, ten or twenty years from now?”

Regarding the question: the significance you attach to something should be commensurate with its importance to your life – meaning your whole life. If you wouldn't attach great significance to something years from now looking back, you shouldn't attach great significance to it now. Doing otherwise is treating the significance of recent things in a biased way.